A frustrated public school parent on another forum recently asked for some information about homeschooling her gifted child. Since her question is very common, I thought I’d address it right here on my blog and maybe others who are sitting on the fence can benefit from the information as well.

Lisa,

Maybe you can help me out. I’m completely fed up with [public school]. My son is very highly gifted and is not receiving any support for his giftedness, he is being kept busy. …

My husband seems to feel I would lose my mind trying to homeschool this very bright and very intense child but I’m beginning to feel there really aren’t many other real options for him. When he was tested at the beginning of grade 2 the psychologist said he was capable of working at grades 7 to 9. I don’t think [public school] will ever be a fit for him and I’m beginning to wonder why we’re subjecting him to all the damage they are inflicting on him by denying his needs.

Could you provide us with an outline of a typical homeschooling day? Is it true that homeschooled children can accomplish more in two hours than classroom kids can in an entire day?? How do you handle the biggest issue, “socialization” ??

Many, many parents of gifted children across North America have taken the plunge to homeschool their gifted children after being let down by their local school board. There is a huge network of support online. Please read my blog article “A Guide for Parents of Gifted Children” and consider joining the Yahoo groups listed at the end. They provide a wealth of helpful information (and moral support). Homeschooling intense kids like ours can be very draining, and it helps to have a safe place to share and vent.

I think that most parents, even those who think they’re going to do “school at home”, ultimately wind up having a school day that, at least in part, is child-led. If your child, like mine, has a lot of intellectual passions, he will want to pursue these and needs time to do so. My eldest makes jaws drop when he talks about astronomy and physics, but I haven’t taught him a word of it – it’s all self-taught.

That said, they can be quite single-minded when they are engrossed in learning about their passions, so I have come to the conclusion that they need at least some structure and some requirement to learn certain core subjects on a regular basis (things like math, French, writing, etc.). I also want them to develop some habits and routines.

You’ll need to find a rhythm that works for you, and that may take a year or two. Someone told me that at the beginning and I thought that was ridiculous, but I’m still figuring things out now at the end of year two, and probably always will tinker with things to find the right fit. That’s not a bad thing, by the way, as you can more appropriately meet the needs of your child if you’re not fixated on doing things a certain way.

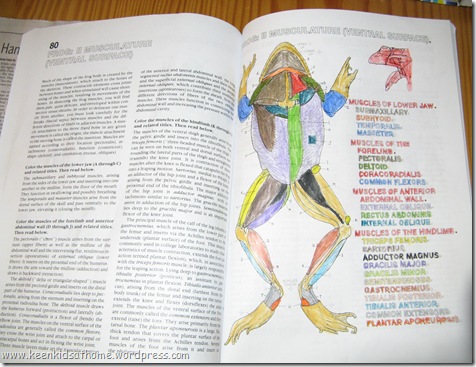

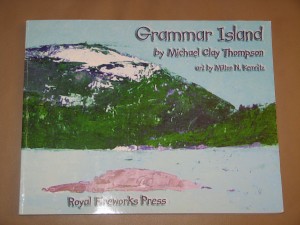

We have been able to meet their needs pretty well, I think. SciGuy, who is strong in math, has essentially skipped from grade 4 math to beginning algebra (and he gets in the 90s or perfect on most of his course work). He wouldn’t get to do that at school. He studies astronomy by watching documentaries and Teaching Company courses taught by university professors. We have a gifted language arts program (reviewed here) that gets him excited about grammar. Yet, he’s a visual-spatial learner and not strong on detail (and hates to hold a pencil), so he works on grade two handwriting and grade-level creative writing. We can meet their needs at whatever level they are at.

A Typical Homeschooling Day?

Well, that varies. A writer and homeschooler named Melissa Wiley once described her homeschool style as “tidal learning”, and that about sums us up too. Some days we’re at high tide and I’m the captain charting the course for our days. After we’ve done that for awhile, and are in need of a change of pace, we move to a low tide style where the kids spend their days poking around in figurative tidal pools, exploring their interests and seeing where they lead. (Melissa describes it much more elegantly than I.)

When we’re at “high tide”, we usually start around 8:45 in the morning with a character-building story or activity. They then have a 90 minute work period during which they do a piano practice, their math and language arts (alternating between grammar, vocabulary, poetry and spelling).

They usually take a break for half an hour or so, and run around outside or play Lego. After that, we have another 90 minute work period, during which we do French or Spanish (alternating days), handwriting, creative writing and one other thing (maybe literature, typing, or geography).

They take another long break over lunch (about an hour), then I usually go outside and do some physical activity with them (basketball drills, badminton, etc.) for another half hour.

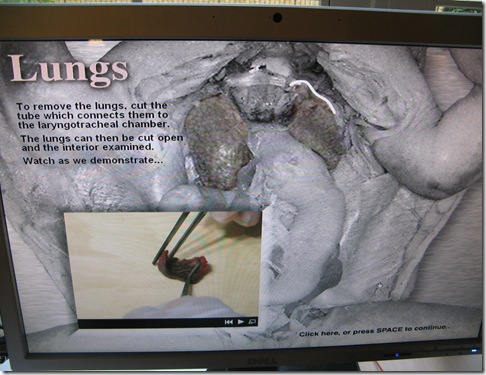

In the afternoons we just do one subject, as the kids often want to explore these in a lot of depth and don’t want to have to switch gears. One day we do history, another is science, then a unit study of some sort (or more history) and nature studies (which usually includes a hike, so it doesn’t feel much like school).

On Fridays we usually do music appreciation, art and Latin instead of the usual schedule, and often they get together with homeschooling friends or go off and do their own research.

Of course, there are weeks when the whole schedule just goes out the window, but these kids are not idle when it comes to learning, and even if I don’t tell them what to do, they almost always choose something educational (researching interests on the computer, drawing maps, reading, looking for bugs outside and then finding out all about them, etc.). Particularly when the weather’s nice, we like to spend time outdoors, go on excursions, etc.

Bear in mind that everyone approaches homeschooling differently and this style may not work for you. I know many parents, whose kids are intrinsically motivated to learn, who don’t schedule anything at all and effectively let their kids “unschool” or choose entirely what they want to learn. For gifted kids, that approach can often be quite beneficial for keeping their love of learning alive, and I encourage my kids to follow their interests as much as possible. I just want to make sure that eventually they will also be able to speak a couple of languages, write an academic paper and do math at the highest levels, so I’m not prepared to hand over the reins entirely!

Even when we have our scheduled days, the kids only do about three 90-minute work periods. In that time, they also get their music practice done, and I don’t make them do homework. By 3:30 they’re done for the day, leaving lots of time for pursuing interests. There is no question that the basics can be covered in a couple of hours; it’s a question of how many subjects you want to include in “the basics”, and for us, that’s quite a few.

Making the Transition to Homeschooling and Dealing with “Socialization”

If your son has had a negative experience with school, he may need some time to “deschool” and find his passion for learning again. In that case, you might very gradually introduce some scheduling, but don’t immediately try to replicate school at home. Give him time to get excited about learning again and also allow him some input into what subjects and topics you will cover if you do start using curriculum.

As for socialization, don’t give it another thought. Everyone trots that out, as though being corralled into groups by age, having to downplay your talents to fit in, being bored to tears, and dealing with brats and bullies is somehow the best way to “socialize” a child. Read “Hold on to your Kids” by Gordon Neufeld to dispel the myths of socialization. Homeschooled kids (especially in large urban areas) have TONS of opportunities to meet other kids. You could spend all your days just going to homeschool co-ops and park days and organized outings for HS kids. I don’t know if people think that homeschoolers just sit in some darkened cellar all day with their noses in their books, but it is nothing like that at all.

I’m biased, of course, but Google “myths of socialization” and you’ll get lots of hits – here’s an article that about sums it up: http://school.familyeducation.com/home-schooling/human-relations/56224.html

Remember, too, that socialization, as defined by the rest of the world, can be a nightmare to a highly gifted kid who is perceived as “different”. And, given that intellectual stimulation is a basic need to such kids, that ought to take precedence over the artificial construct that is “socialization.”

Filed under: Giftedness, Homeschooling | Tagged: education, gifted, homeschooling, public school, unschooling | 12 Comments »